David Baker (University of South Carolina, 2000) remembers loving music at a young age. He wanted to be in a rock band, like Mötley Crüe and Guns N’ Roses.

“Music has been a lifelong journey. I was always into music ever since I was a young, elementary school-age kid. I started getting into anything from the Beastie Boys to Guns N’ Roses and a lot of that late ‘80s music. I guess you could call it metal, but it was hair metal.”

It wasn’t until junior high that Baker would pick up the guitar. Baker played guitar in a couple of bands through high school and college, but nothing took off. It wasn’t until Baker and two of his Theta Eta chapter brothers formed a band that he would get traction in the music industry. The band recorded a record and signed to a small indie label in Los Angeles. The record did not do very well, and the label later dropped them.

“When we realized we weren’t going to be rock stars or make a living from that, I had to make a choice,” Baker said. “I was like, ‘Well, do I just stop making music, or do I try to transition into something else?’”

Baker always enjoyed the recording process when his bands were in the studio, and he had a background in recording with his media arts degree. He decided to stick with music but transition into studio work.

For the first couple of years, Baker was only able to work part-time in the studio until a friend offered him a job at a label he was starting. After saving some money, he packed up and drove from South Carolina to Los Angeles.

“We started doing a lot of rock stuff, and then we moved on to electronic music when all the pop craze hit. Then the studio transitioned to writing music for sync placements for commercial or just background music for a game show or a movie or a T.V. show. When they started moving in that direction, there wasn’t a place for me. I wasn’t a studio musician. My focus was on engineering,” Baker said.

Baker made a name for himself as an engineer and left the label that brought him to L.A. after being with them for six years. “I’ve always been a for-hire guy. That was just the main spot I worked out of. While I was out there, I had a lot of side gigs,” Baker said. “Once you start to meet some people and work and pay some dues, you pick up jobs by saying, ‘Hey, you need a guy? I know a guy.’ It’s all that word of mouth way of getting gigs.”

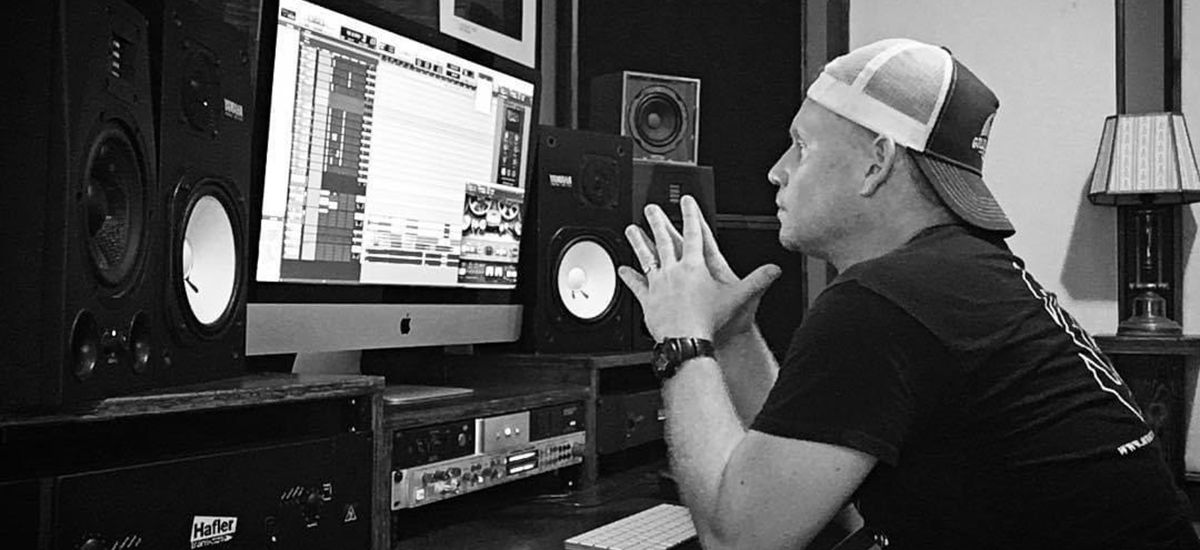

After ten years in Los Angeles, Baker and his wife decided to move back to South Carolina to raise their son closer to family. He turned his basement into a studio so he could keep working with artists and labels he made connections within L.A. He now works from a custom-built mix room, which takes up the whole lower half of his house and splits time between Los Angeles and Nashville mixing, engineering and producing.

“The biggest transition for me was figuring out how I continue to work on the things I want to work on and work with the people I want to work with while continuing to get new records and new clients, despite not being in the thick of things,” Baker said. “It took a little while. Like anything else, the business ebbs and flows, and you have to be prepared for that. Other than that, it wasn’t a big culture shock moving back.”

Q&A with David Baker

What was it like getting started in studio work?I never ever got a gig, based solely on my skill set. Out there, your skillset has to be good, or you won’t survive. You have to work on that, and I spent my first few years out there figuring out what I was doing, continuing to learn and get good and get fast. There are many times I went to big studios, and I didn’t know what in the world was going on in there, but I sat down, and I just fought through it. And at the end of the day, I was like, ‘I can’t believe I’m still here, and they didn’t fire me.’

What is your process from getting the files to completing a song?

What I do currently and I want to continue doing for years and years is just mixing records. Once something is recorded, all the individual instruments, the vocals, the backing vocals, everything they want in the song is recorded, they send it to a guy like me. I will put all the pieces together and make them sound cohesive as one song instead of 125 instruments.

I get everything individually and just put all that together and balance it out and try my best to make it sound as professional and as good as it can within the artist’s direction.

If they want the drums to sound real trashy, I don’t want to make them sound polished. If they wanted the vocals to sound distorted and old school, I do that, or sometimes they’ll track them like that. Then once I do that, I’ll send them a mix. If they have any revisions like ‘Hey, I’d like the vocal up a little bit or the guitars up a little bit,’ or, ‘Can you adjust so-and-so and so-and-so,” I’ll make all the adjustments that they want, and then we’ll send it to a mastering person.

The mastering person puts the final polish on it. They make sure all the levels are proper for streaming or radio play. The mastering is the last touch before it goes out into the world.

Working in an industry with big names, how have you been able to stay grounded?

I don’t like talking about myself. I don’t like bragging. I don’t like name-dropping, and I do it sparingly. I learned from a guy I did a lot of work with, who I consider one of my mentors. He told me, ‘In Los Angeles., when you get out there, the entertainment business is huge, but the circles you work in are tiny.’ The business itself is a global industry, but the people that make all these things run in small circles. Within two minutes of talking to somebody, you can tell if they’re really working, kind of within the circle, or on the outside, just trying to climb through a window or a crack in the wall. A lot of that has to do with someone saying, ‘Oh, I’ve worked with so-and-so and so-and-so.’

When I have to talk about specific people I’ve worked with, which I don’t really like to do, I tell people, ‘Hey, I’ve worked on these records that I really enjoyed, and they did very well. I’m very grateful to have been a part of them.’ Because all of this is just by chance, I ended up in all those rooms by chance or because I knew someone and I worked hard, but still, it’s by chance. So, if you’re dropping a lot of names, it’s like you’re trying too hard.

What has been a fun project you have worked on recently?

I really liked working on one record by an artist named Cozz, and he was signed to J. Cole’s label. We mixed his first two records, but the first one is called Cozz and Effect. That was a really cool record because it was a kid that’s just basically coming straight out of South Central, Los Angeles.

Another cool project was for a band called The Frights. It was called Everything Seems Like Yesterday. They went up to a cabin outside of Los Angeles in the mountains, and everything they recorded on this record was this weird, quirky stuff. And nothing was sampled. Nothing was a synth. If they needed a click sound, they went outside and clicked a stick against the porch railing, and they made music that way. That one was super cool.

All the big records I worked on were great, like the first Billie Eilish record we worked on, a song came called “Bellyache.” I was working with a guy named Rob Kinelski, who won four Grammy’s last year, mixing her second record, which was right when I moved back. It was a friend of his that just said, “Hey man, I’ve got this mix that’s just not coming through. Do you mind working on it?” So we went in and worked on it, and I was like, “Man, this is like some different stuff.” You never know if anything is going to blow up.” You never expect it to be platinum or gold or a number one record.

What project did you work on that you had no idea was going to blow up?

Kinelski and I were working on a mixtape for Big Sean, and it was like three or four songs, and one of them was, “I Don’t F— With You.” It was just a mixtape song, so we mixed it. He had a couple of revisions and sent a couple of new things to fly in. We were both sitting there sweating because we had to catch flights out the next day for the holidays. So at the umpteenth hour, at two in the morning, the mix was approved. We send it to New York to be mastered. They mastered it that night, and they put it out a couple of days later. So we finished the mixes, and we both jumped on a plane. Three months later, it’s a platinum number one record. Δ